In this post we will discuss the basics of Object Oriented Programming and how they are implemented in Golang.

As everybody knows, Go is peculiar. In my opinion it is caused by the ambition to be transparent, simple and fast. In a previous post, we compared how differently Golang works with string when compared to C++.

For all the major concepts of OOPs, we will first have a brief discussion to get a basic understanding and then we will see how they are implemented in a purely OOPs language such as Java. This would give us a right base see the difference when trying to achieve the same in Golang.

OOP: Formal Definition

From Wikipedia: From Wikipedia: “Object-oriented programming (OOP) is a programming paradigm based on the concept of “objects”, which can contain data, in the form of fields (often known as attributes or properties), and code, in the form of procedures (often known as methods).”

OOP: A Simpler Definition

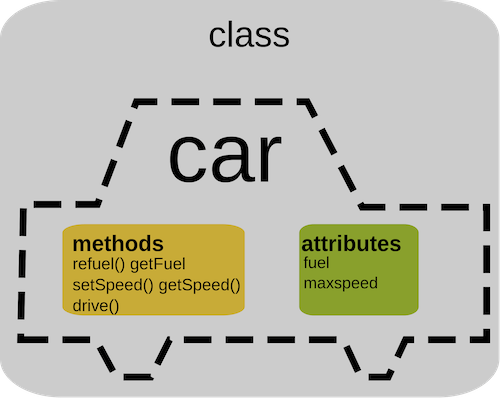

If you could understand the definition from Wikipedia, well and good. But if you are new to this- let us see it with the famous “everything is an object” view. Everything in the world can be classified into classes- for example, you and I are objects of the class “human”. For a better understanding, let us focus our discussion on the human class only. Every Human has two types of features: state (fields) and behavior (methods). Similarly, an Object in the OOP paradigm has attributes and methods.

1. Fields (attributes)

You and I both are humans, but we are different. What makes us different? Height, weight, eye color, etc. So, Human is a class, and once we set different values for the attributes(height, weight, eye-color,…an infinite list in case of humans…) of this class- it becomes an object. Hence, you and I are different objects from the class human because we have different values of the attributes that define a human.

In other words, these attributes define the state of an object. Imagine a String class, what can be the attributes for it? Umm, pointer to the character array, length of the character array, etc. If I have two different String objects, they will have different values for the pointer and the length.

A class becomes an object once the values for the fields are initialised.

2. Methods (behaviour)

We are now clear that you and I are different objects from the same class human. But we perform a lot of similar tasks- breathing, eating, blinking the eyes, etc. These behaviors can change the state of a human. For example, if I eat a lot, my weight may increase. Hence, behaviors or methods can change the state of a human.

Coming back to the String class example, what methods come to your mind- appending to the string, erasing characters from the string, returning the string’s length, etc. Some of these will also change the values of the attributes; for example, the length will change if we insert more characters to the string.

Methods may change the state of the objects.

Let us move towards the technical side now, in object-oriented programming, everything is an object. As we have seen, an object has two types of features- attributes and methods. Java is a very popular example of an OO language. C++ does not enforce OOP. However, you can achieve both procedural and object-oriented programming in C++.

Those coming from C++ will find it strange that we have the Integer class in Java (everything is wrapped in an object, even int). The Integer class wraps a value of the primitive type int in an object. An object of type Integer contains a single field whose type is int.

Let us write a simple class in C++. I am choosing C++ only for the definition of classes and objects, because most of the readers of my blog prefer C++, but later on in the tutorial, we will consider Java.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

class Human {

public:

// The attributes

int weight;

int height;

int age;

// The methods

int breath() {

printf("A human of age %d is breathing", age);

}

int HappyBirthday() {

this->age += 1; // this is a pointer to the current object

}

};

int main() {

Human me; // A human is initialised

// Let us set the attributes for "me"

me.height = 175;

me.weight = 70;

me.age = 22;

// I get one year older

me.HappyBirthday();

std::cout << me.age; // Shall print 23 which is 22 + 1

}

// OUTPUT:

> 23

An object(?) in Go

We have our first point of comparison. How do we define objects in Go? In Go, data and functions are kept separate. There are no classes in Go, just structs which can only store data and do not have any methods. But we can achieve methods using receivers (notice the () block right after func).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

type Human struct {

Height int

Weight int

Age int

}

func (h *Human) HappyBirthday() {

h.Age += 1

}

func main() {

me := Human{ Height: 175, Weight: 70, Age: 22 }

me.HappyBirthday()

fmt.Println(me.Age)

}

// OUTPUT

> 23

Moving forward to Real Business

So far, we were more concerned about what OOP is and less about the comparison with Go. Now that the pre-requisite is met, we can continue the discussion.

There are three phenomenon in OOP,

- Encapsulation

- Polymorphism

- Inheritance

Our real comparison will be based on how we deal with these three things in Java vs to that in Go.

1. Encapsulation

When we defined our “Human” class in C++ above, did you notice that we had the term public before everything?

Encapsulation, in short, is controlling access to the information of an object. For example, a human might not be want to expose his/ her age to other objects. Similar thing can be achieved while making a class in programs. We control this access using access modifiers. These are:

-

public: Methods and attributes that use the public modifier can be accessed within your current class and by all other classes.

-

protected: Attributes and methods with the access modifier

protectedcan be accessed within the class, by all other classes within the same package, and by all subclasses within the same or other packages. We will see what subclasses are later inInheritance. -

private: This is the most restrictive and commonly used access modifier. A

privateattribute or method can only be accessed within the same class. Subclasses or any other classes within the same or a different package can’t access a private attribute or method. -

No modifier: What if we do not provide any modifier at all. In such cases a language-specific default is used. In Java, this defaults to package-private or access within the same class and by all classes of the same package. I C++, the default is

private.

So, I am assuming you have understood how we achieve encapsulation in Java or C++, just by adding one of the modifiers before the attributes/methods. I will still write the Java code for you below, also refer the C++ code above.

Encapsulation in Java

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

//A Java class which is a fully encapsulated class.

//It has a private data member and getter and setter methods.

package com.encapsulation;

public class Student{

//private data member

private String name;

private String college = "IIT BHU";

// method to get a student's name

public String getName(){

return name;

}

// method to set a student's name

public void setName(String name){

this.name=name

}

}

It makes complete sense to have a small discussion on the above written Java Code. There are two attributes: name and college and both are private. This means that we cannot modify or access them directly. We also have two methods, getName() and setName(), both are public and we can access them from anywhere.

So, to set a student’s name we can call student.setName("Arjun Salyan") and to get a student’s name we can call student.getName(). This will work because private attributes can be accessed by the methods of the same class.

Notice that, we cannot modify college of a student because the attribute is private and there is no method that will help us modify it. I hope you can now think of the use cases and really appreciate encapsulation.

Encapsulation(?) in Go

Hmm, so can we have something similar to encapsulation in Go? Yes and No. First of all, there are no access modifiers in Go. All we have are exported and unexported fields. Any method or field whose name start with an uppercase letter are considered exported in Go, while lowercase are unexported.

An exported field or function can be accessed “directly” from other packages, while unexported cannot be. And that is it. I will write two structs below, first one has exported fields and other does not.

NOTE: Unexported fields cannot be accessed directly from other packages. This does not mean that we cannot access them at all. It is just that we cannot access them directly, I hope you can now figure out on your own what I mean by this (think of methods)!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

package data

import (

"fmt"

)

type ExportedFields struct {

Field1 string

Field2 string

}

type unexportedFields struct {

field1 string

field1 string

}

func(f *nexportedFields) NewUnexportedFields(val1, val2 string) *unexportedFields {

return &unexportedFields {

field1: val1,

field2: val2

}

}

Very Important that we discuss this code. There are two structs, ExportedFields and unexportedFields. ExportedFields starts with uppercase and hence it can be accessed from other packages- initialisation and modification both can be done from anywhere.

But unexportedFields is different, neither the package nor the internal fields have been exported. So, let’s say we want to create an object of type unexportedFields from any other package, how do we continue? Simple, write a method that returns a created object and export the method.

In the above example, NewUnexportedFields is a function that is exported and can be access from anywhere. We use this to create new objects of the type unexportedFields. See below

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

package main

import (

"data"

)

func main() {

myObject := data.NewUnexportedFields("value_for_field_1", "value_for_field_2")

}

That should be enough for encapsulation. We have learnt encapsulation and how to achieve something similar in Go.

2. Inheritance

To explain inheritance, I will fall back to the previous “human” example. Let’s try to make subclasses of humans based on profession: “Doctor”, “Engineer”, “Writer”, etc. All of these subclasses will have the properties of the class human but in addition they may have properties of their own.

The idea behind inheritance is that we can create new classes that are built upon existing classes. When we inherit from an existing class, we can reuse methods and fields of the parent class. Moreover, we can add new methods and fields in our current class also.

We should not forget the role encapsulation will play here:

- Public methods of the parent class are also public in the subclass.

- Methods declared protected in a superclass must either be protected or public in subclasses; they cannot be private.

- Methods declared private are not inherited into the child class at all, so there is no rule for them.

Inheritance in Java

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

class Human {

public int height;

public int weight;

public int age;

public void Breathing() {

System.out.println("Human is breathing");

}

public void Eating() {

System.out.println("Human is eating");

}

}

public class Doctor extends Human {

public String nameOfHospital;

public void Working() {

System.out.println("A Human who is a Doctor, is saving lives.");

}

}

Well, a doctor will have some height, weight and age. He will also breath and eat. So, instead of defining them separately we can directly inherit these properties from the Human class. This comes in handy becuase classes can be reused now.

Let us move to Golang and see inheritance there.

Inheritance(?) in Go

To be technical, go does not support inheritance, instead it does composition. This means, putting together all the fields. So, when I define a “Doctor” struct, I can simple put together fiels from Human struct and add more. Let’s see an example.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

type Human struct {

weight int

height int

age int

}

func(h *Human) breathing() {

fmt.Println("A Human is Breathing")

}

type Doctor struct {

Human

nameOfHospital string

}

func(d *Doctor) working() {

fmt.Println("A doctor is saving lives")

}

func main() {

doctorA := Doctor{

Human: Human{175, 70, 22},

nameOfHospital: "HospitalA",

}

doctorA.Human.breathing()

doctorA.working()

}

// OUTPUT

> A Human is Breathing

> A doctor is saving lives

I hope you noticed that I could also call the methods for the Human struct. We can also name the inherited struct if we want.

1

2

3

4

type Doctor struct {

human Human

nameOfHospital string

}

Inheritances does not end here. Overriding the methods of the parent class is another concept, but in my opinion it would be better understood if take care of that in the Polymorphism.

3. Polymorphism

Polymorphism happens to be my favourite. And my favourite way to explain polymorphism is the classis “Shape” example. Please read next paragraph carefully if you are new to polymorphism.

Imagine that we have a class Shape with two attributes: area and perimeter. The class also has two methods calculateArea() and calculatePerimeter(). Both of these methods will calculate the area and perimeter of the shape we define and update the fields with their values.

BUT, the way we calculate area for different shapes is different. For a square it is side*side and for a circle it is pi * radius * radius. This means that a single calculateArea() method will not be enough to calculate the area for any shape we provide. This is where polymorphism comes into picture.

Polymorphism is the ability of an object to take on many forms. In other words, in polymorphism behaviour may change according to the objects.

Overriding in Java

In inheritance we saw that the method of the parent class are also inherited. But what if want the methods to behave differently for the new(child) class. Easy, we can simply override the methods. Let’s see how.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

class Human {

public void speak() {

System.out.println("A human is speaking.");

}

}

class Doctor extends Human {

public void speak() {

System.out.println("A doctor is speaking"); // overriden

}

public void work() {

System.out.println("A doctor is working");

}

}

public class TestDoctor {

public static void main(String args[]) {

Human a = new Human(); // Human reference and object

Human b = new Doctor(); // Human reference but Doctor object

a.speak(); // runs the method in Human class

b.speak(); // runs the method in Doctor class

b.work();

}

}

// ERROR

error: cannot find symbol

b.bark();

^

b.work() throws an error, easy to understand. We will get compile time error since b’s reference type Human doesn’t have a method by the name of work(). Referencing Doctor would fix the error, what I wanted to show was that the method got overriden even if we reference it as Human.

So, this explain how we can change the behaviour according to the subclass.

Virtual Methods in Java

Nothing new here. But a Virtual function in Java is expected to be defined in the derived class. We can call the virtual function by referring to the object of the derived class using the reference or pointer of the base class.

We can go on and on. There are a lot more complexities here when it comes to Java. While this is different in Go- simple and simple. So that we do not leap out of the scope of this post, I will stop exploration of Polymorphism here and move on to Golang.

Interfaces in Golang

Like every other example, Go does not have overriding or virtual functions. And that is actually good- helps to keep things simple. But this does not mean that we need to compromise on functionality.

We have interfaces in Java or any other language. But in Go, interfaces is all we have when it comes to achieving polymorphism. Let’s see how and let’s finally solve the problem we faced earlier- calculation of area for different types of objects.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math"

)

// Our interface with the two methods

type Shape interface {

area() float64

perimeter() float64

}

type Square struct {

side float64

}

type Circle struct {

radius float64

}

func (s Sqaure) area() float64 {

return r.side * r.side

}

func (s Square) perimeter() float64 {

return 4 * s.side

}

func (c Cirlce) area() float64 {

return math.Pi * c.radius * c.radius

}

func (c Circle) perimeter() float64 {

return 2 * math.Pi * c.radius

}

func measure(s Shape) {

fmt.Println(s)

fmt.Println(s.area())

fmt.Println(s.perimeter())

}

func main() {

s := Sqaure{side: 3}

c := Circle{radius: 5}

measure(s) // This will use functions for the square

measure(c) // This will use functions for the circle

}

OUTPUT:

{3}

9

12

{5}

78.53981633974483

31.41592653589793

This is also called dynamic binding in OOPs. Depending on the type of object, the relevant function gets called.

Are you able to appreciate now why Polymophism is my favourite?

Let’s Evaluate

What we have seen here is a very small discussion of the major topics of OOPs. But while comparing with Golang, I can’t think of any other topics, Golang just does not have them. Go tries to keep things simple while maintaining that we achieve the required functionality. I have always found a way to achieve everything I could do in any other language. However, the design and thinking process needs to be changed while solving problems with Golang.

OOPs is a challenging paradigm in itself. Anyone switching from years of procedural programming will find it challenging to work with the heavy concepts of a language like Java. But for Go, I leave it up to you to decide if the implementations are difficult. Just a hint: we have seen almost every related topic in Go, we have left almost everything in java XD. I hope the post was useful.

I hope the post was useful.

Comments